Every day, without thinking much about it, I turn on the tap and clean water, safe to drink, flows out. Perhaps I should pay more attention, because not so long ago, that would not have been the experience of residents of The Hague. Join me in taking a look at the history of our The Hague Water Supply (Duinwaterleiding).

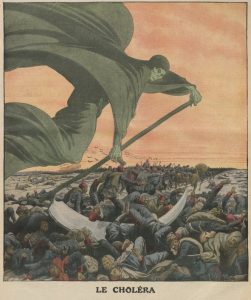

First case of cholera

The relationship between poor drinking water and cholera had not yet been established. After all, scientists like Pasteur and Koch didn’t discover the existence of bacteria until the last quarter of the 19th century.

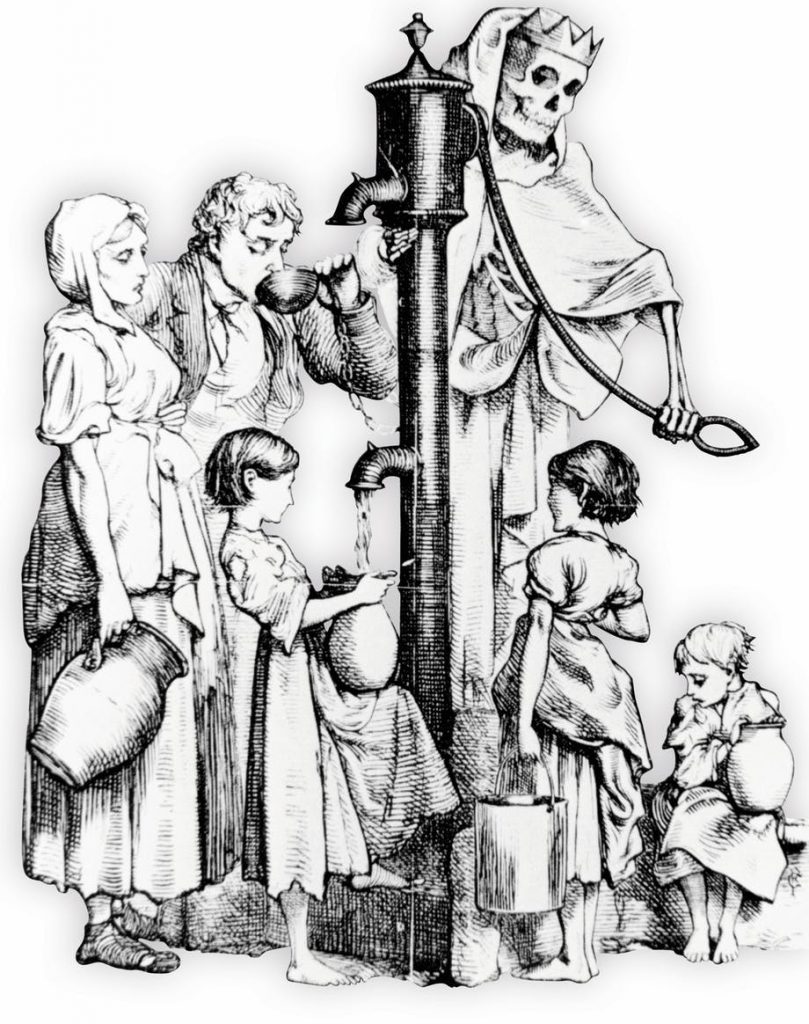

Drinking water

Residents of The Hague had to get their drinking water from pumps that often produced dirty water. The wells were often not dug deep enough, resulting in groundwater supplies that were contaminated with droppings and street dirt. People also used rain barrels, but the water flowed into them through polluted gutters and pipes.

Several cholera epidemics followed, of which 1866 was the worst. In The Hague 710 people died (around 1% of the population) and in Scheveningen 306 people (around 3.7% of the population).

Corrective measures had been called for earlier, but only after this epidemic did the administrators of The Hague acknowledge that they had to do something. At the council meeting of September 26, 1871, a majority was in favour of a plan to construct a water supply system at the municipality’s expense.

The Hague Water Supply

Shortly after this council meeting, the municipality asked engineer J.A.A. Waldorp to draw up a plan for the water supply. Norwegian engineer Th. Stang and architect L.A. Brouwer joined his team. They developed a scheme for extracting water from the dune area between Scheveningen and the Wassenaarse Slag. In 1872 the municipality received the necessary land on leasehold from the State and the execution of the work could begin.

The run-up may have been slow, but the implementation of the plans went swiftly. On October 24, 1874 the first dune water arrived at the customers. Th. Stang had meanwhile been appointed director of the municipal water supply company. However, it was only after 10 years that he was able to report that the company was making a profit, but “The profit, however, was first and foremost in human lives that would otherwise have been prematurely lost to infectious diseases.”

The complex

Extracting water required construction of a large complex in the dunes. This included a pumping station, canals, and large sedimentation reservoirs. The pumps were steam-powered, requiring a separate building to house the boilers, and yet another to store the coal that fuelled the boilers.

The most striking feature was the high reservoir (a structure commonly known as a water tower) used to build up enough pressure to get the water to the houses in The Hague.

In 1886, the Kurhaus caught fire. Because of insufficient water pressure, the fire brigade could not extinguish this fire. In order to prevent such a situation from occurring again, some changes were made in the water tower.

Connections and capacity growth

By October 1875, 5584 properties, 2977 of which were alms-houses, were connected to the dune water supply. However, not everyone had a connection at home. For example, at the end of the 19th century the approximately 60 homes of Paulus Potterhofje had to share one tap.

When Waldorp designed the water supply system in 1871, he assumed that The Hague would never have more than 100,000 inhabitants, but that proved not the case. This number was already reached before the Duinwaterleiding was finished. Around 1900 it became clear that more water was being taken from the dunes than was resupplied by rain.

With various technical adjustments and expansion of the extraction area, it was still possible to meet the growing demand. The organization also grew, and in 1909 an administration building with a garage and workshops was opened on Buitenom. The organization also had other buildings elsewhere in The Hague.

Water from elsewhere

In the early 1930s there was some talk about taking water from the Rhine (or actually: the Lek) and filtering it through the dune sand. Due to various reasons, including the Second World War, this plan only became reality in 1955. Queen Juliana presided over the festive opening.

In the sixties, the Rhine water became increasingly dirty. At the same time, Hagenaars were using more and more water, partly thanks to the washing machine and the daily shower. So it was necessary to relocate the tap to the Afgedamde Maas. In 1976 it was Queen Juliana’s consort, Prince Bernhard, who put the Maas water pipeline into operation.

The buildings

The complex in the dunes has been regularly adapted to increasing demand and technical developments. For example, the steam engines were replaced by electric pumps, the last in 1949. The buildings also suffered from the influence of the salty sea wind, requiring various restorations. The water tower and the machine building have now become state monuments.

Dunea

Over time The Hague Duinwaterleiding merged with sister institutions in Delft, Westland and Leiden in the ‘Duinwaterbedrijf Zuid-Holland’. The entire dune area between Monster and Katwijk is now infiltrated with water from the Afgedamde Maas.

And we get the bill for our water use from ‘Dunea’, the name since 2009. Of course, the company does more than send bills. It ensures that clean water comes out of our taps every day — a benefit that our ancestors could only dream of and which unfortunately is not yet a reality for many people in the world.

I tell the story of the importance of good drinking water during my bike tour from City to Sea